Crete Minoan Civilization

Crete Minoan Civilization

One of the great traditions of modern Crete is…ancient Crete. The island’s history and archaeology have been an appealing subject, a scholarly calling and an expanding local industry since at least the last decades of the 19th century. Catering to a public seemingly never tired of such stories, media headlines often touch on the island’s distant past. The archaeologist Arthur Evans sailed to the island in 1894 as a curious, well-heeled history buff pursuing a mysterious prehistoric script. At Knossos, he found its source. He also discovered a lifelong passion, a career and an avenue for sharing his own worldview of both the past and the present. Just as, in antiquity, all Cretan roads led to Knossos, so too, after Evans’ excavations began in 1900, have all things Minoan essentially begun there. Whether or not Knossos “owned” the entire island under a single powerful king, perhaps memorialized in the “King Minos” of later legend, it certainly became the most powerful palace at a time when an island-wide Minoan network of administrative, storage and export centres put their timeless stamp on the histories of Crete, its Aegean neighbors and its distant trade partners east and west.

MANAGING ISLAND RESOURCES

Crete’s first monumental buildings rose at Knossos, Phaistos and Malia, while smaller settlements sprung up around the island as well. During Middle Minoan/Late Minoan times (1750-1490 BC), a devastating earthquake (ca. 1700 BC) meant the main palaces had to be completely rebuilt, setting the stage for the culture’s greatest era (17th-15th c. BC). Further secondary centers were founded at Kydonia, Archanes, Galatas, Gournia, Petras (Sitia) and Zakros. Independently, or as part of a later, more unified system, these sites served as collection and redistribution points for agricultural crops, craft products, artistic works, and other commercial goods.

DISRUPTIONS AND RENEWAL

Minoan history is marked by a series of natural disasters or major social disruptions, the first of which was the volcanic eruption of nearby Thera (Santorini) – now newly radiocarbon-dated from a charred fragment of olive wood to the early 1500s BC. More consequential was a fiery event in about 1490 BC, when all of Crete’s secondary Minoan centers or settlements were destroyed, perhaps through a violent takeover led by a core group of local elites, or by an invasion by forces from the Greek mainland. A newly formed elite class of Minoans/Mycenaeans now ruled the island from virtually unscathed Knossos, with an increasing mainland influence detectable in Minoan art and religion. This “Third Palace Period” was a time when Crete enjoyed its greatest overseas influence. Homer retrospectively describes Late Bronze Age Crete as “a land…in the midst of the wine-dark sea, a fair, rich land, begirt with water; and therein are many men, past counting, and ninety cities.”

AFTER THE PALACES

Around 1370 BC, Knossos was also destroyed; it would be approximately 400 years before it was repopulated. During the subsequent “Post-palatial” period (1370-1100 BC), Crete’s outlying administrative centers, towns and villages became more independent, as the island’s now-fully-Mycenaean overlords ruled not from Knossos, but the mainland. Many native Cretans relocated inland to more defensible sites, where they could better protect themselves from an increasing inflow of Hellenic immigrants. Nevertheless, Crete remained a sea power, sending, according to Homer, a contingent of eighty ships to aid in the Trojan War.

AN INTERNATIONAL CAST

Political turmoil and the rugged natural landscape were obstacles to early archaeological attempts in Crete, but perhaps the greatest obstacle was the reluctance of government officials to issue permits. In 1879, Minos Kalokairinos, a lawyer, businessman and antiquarian from Irakleio, hired twenty workers and simply began digging. He was stopped by the authorities three weeks later, but not before he had revealed portions of the palace’s West Wing and West Magazines. Soon, others appeared, too. Heinrich Schliemann himself joined the throng in 1886, hoping to buy the mound, but was deterred by its Turkish landowners’ exorbitant demands. Evans, less concerned with cost, purchased 25% of Knossos in 1894, then the remainder of the palace area in 1900. Early excavations at the other main Minoan palaces – Phaistos (1884, 1900-1904) and Malia (from 1921) – were launched by Italian and French scholars. Harriet Boyd-Hawes, an American female pioneer in Greek archaeology, led the first excavations at Gournia in 1901-1904. Notable Greek archaeologists in Crete have included Spyridon Marinatos, Nikolaos Platon and Yiannis (J. A.) Sakellarakis.

LARGE AND SMALL

Knossos was by far the largest, most monumental Minoan center on the island. During the Late Bronze Age, the palace grew to include over 1,500 rooms, rising 3-4 stories and covering an area of about 20,000 square meters. The city around it was also enormous, occupying some 750,000 sq.m. Comparatively, the Phaistos and Malia palaces reached only about 10,000 and 7,500 square meters. The secondary centers had far smaller scales, as we see at Kydonia (Hania), in the west, and Zakros, in the east. The smallest complexes, or country “manor houses,” are exemplified by Myrtos-Pyrgos, west of Ierapetra, or Vathypetro, south of Archanes, where a wine press and pottery kiln have been found.

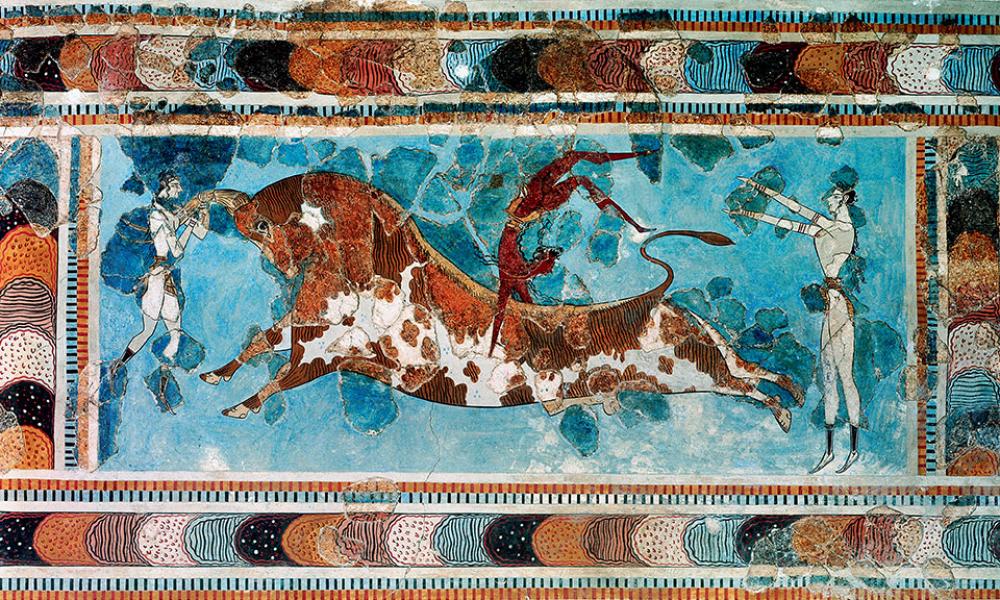

SHARED CULTURAL IDENTITY

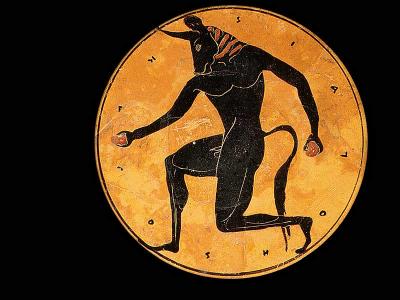

Minoan centers exhibit a cultural consistency both in architectural features – including ashlar masonry, light wells, shrines, storerooms, multiple floors with staircases and courtyards – and in the extraordinary artifacts unearthed. Characteristic Minoan objects at the Archaeological Museum in Irakleio include masterpieces such as the Harvester Vase, Knossos Snake Goddess figurines, the Phaistos Disc and the painted Aghia Triada sarcophagus, as well as stunning gold jewelry, wall paintings, inscribed tablets and signet rings and engraved stone seals, with imagery alluding to a central female deity; animal sacrifice; and daemonic creatures symbolizing the dark side of nature beyond human control.

FROM THE BOTTOM UP

For much of the 20th century, Minoan Crete was viewed as a place of peaceful, proto-literate people, without wars or need of more than a merchant navy, who lived in sophisticated palaces and cherished nature, art, religion and commerce. The focus was on the elegant, luxurious lives of palace-based Minoan elites. Now, however, old myths and interpretations are being swept away. Previous palace-centric studies of Crete’s Minoan past have provided only a narrow glimpse of the full spectrum of Minoan society. At Knossos, after decades of investigation, only 2% of the entire Late Bronze Age city has been excavated. In contrast, today’s researchers are expanding their studies to look instead at ordinary Minoans and how they lived. By combining landscape surveys, targeted excavations and interdisciplinary scientific analyses of diverse evidential materials, archaeologists working in Crete are now developing a “bottom-up approach.” The complex picture currently emerging is no longer one of a hierarchical series of palaces controlled by Knossos, but of individual polities competing with each other, heavily influenced by socio-religious ideologies emanating from Knossos and involved in Knossos-led economic interactions. But these were only firmly unified under a single (external) authority in the final stages of the Late Bronze Age, after 1370 BC. What’s more, the Minoans knew warfare, as telltale clues indicate, including weapons in shrines, tombs and residences; the existence of settlements in defensible positions; and the 2009 discovery of long coastal walls at Gournia that may represent fortifications.

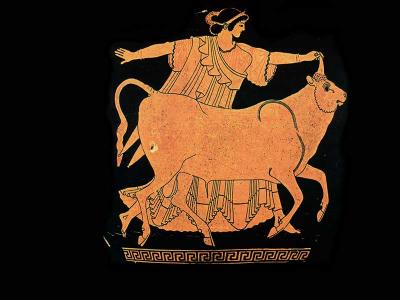

Among the many female figures in Cretan myths, foremost is Europa, the first queen of the island. One of Zeus’ conquests, she was a Phoenician princess abducted from Tyre and borne to Crete on a handsome white bull (Zeus). On arriving, Zeus revealed himself and gave her gifts, including Talos, a gigantic bronze automaton tasked with guarding Crete. Europa bore Zeus three sons, Minos, Rhadamanthys and Sarpedon; Minos became king of Knossos and ruled the island. Thus, Europa was the founder of Crete’s leading family.

HUMBLE RUINS

Following the final collapse of Crete’s Bronze Age civilization (ca. 1000 BC), Iron Age city-states gradually arose. However, Crete only returned to peace and prosperity after Rome’s annexation (1st cent. BC), with Gortyn becoming the island’s capital. Knossos, a community marked by affluent villas in the 2nd century AD, eventually declined during medieval times. In 1857, a French scholar lamented that the area of Knossos, “the oldest city of ancient Crete,” was marked by “one miserable village, whose name, Makrytichos (Long Wall), informs the antiquarian that there were once great constructions here; but…[now]…only …vague, formless…mounds of bricks.” If he could only see the site today!